Pack Houses: An opportunity to promote trade in ‘Fruits and Vegetables’ and beyond

What are pack houses?

Since the 1980s, international trade of fruit and vegetables has been growing by leaps and bounds, driven by rising incomes and the expansion of the middle class worldwide. In 1988, world exports of fruits and vegetables amounted to US $21 billion; by 2015, the value jumped more than ten times to US $215 billion. Motivated by this growing global demand, developing countries actively pursue the production and export of this high-value agricultural subsector to capture a large portion of this market. However, the adoption of rigorous phytosanitary regulatory standards in the industry has made the entry into international markets, particularly in developed countries, highly prohibitive.

In general, all countries maintain sanitary (human and animal health) and phytosanitary (plant health) standards to ensure that food is safe for consumers, and the spread of pests or diseases among animals and plants is prevented. The phytosanitary measures ensure that vegetables and fruits are not subject to specific treatment, and do not contain more than permitted levels of pesticide residues or harmful organisms. These measures apply to both food products produced locally as well as those imported from other countries. But, in international trade, due to their technical complexities, they may result into high trade restrictions. To discourage the member nations from adopting this practice, the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) which came into force in 1995 sets out the basic rules for food safety and animal and plant health standards in imports of products. Member countries are encouraged to use international standards, guidelines and recommendations where they exist to address arbitrariness and in-transparencies. However, it allows members to use measures which result in higher standards if there is scientific justification. These standards therefore differ across countries and may act to restrict trade. These standards are particularly high in developed markets making it challenging for developing countries to comply with these standards.

To meet this challenge in the export of fresh fruits and vegetables, most countries are now increasingly focusing on setting up state of the art pack houses and strengthening the health and safety protocols in them. The pack houses are specialized physical structures where harvested produce is consolidated, treated and prepared for transport and distribution to markets. The pack house is the focal point of a farm business which maximizes economy of scale, improves market access, and facilitates technical and business development interventions. The global trend is to get the pack houses certified to be compliant with the SPS of major importers of horticulture and route exports particularly to demanding markets through these pack-houses.

Benefits of pack houses

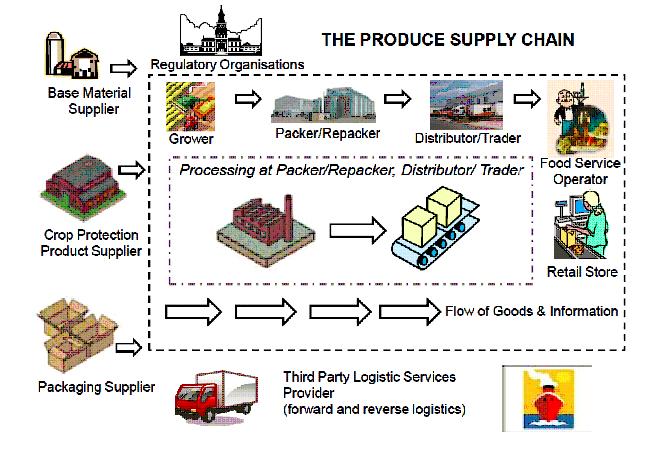

The model of pack houses is illustrated in Figure 1 below. It shows that a pack house is a link between the grower and market that can be used as a single platform for aggregating the products, cleaning and processing them under the supervision of plant quarantine personnel, examinations/testing of export consignments, and certification.

Figure 1: The produce supply chain and the pack house

Source: Adapted from ‘Traceability for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables Implementation Guide GS1, Issue 2, May-2010

A state of the art pack house is committed to continuous innovation and improvement of our processes in order to ensure high quality and meet the standards set by the market. Several private players have emerged offering auditable certification for world class safety standards for fruits and vegetables. These are for instance,

• Global gap: It covers all stages of production, from pre-harvest activities such as soil management and plant protection product application to post-harvest produce handling, packing and storing and is now recognized in over 100 countries. This is the minimum requirement in EU markets.

• British Retail Consortium global food safety standards: It guarantees the standardisation of quality, food safety and operational criteria throughout facilities, ensures that they fulfil their legal obligations and provides protection for the end consumer.

• TESCO produce pack house standards (TPPS) : It is a manufacturing standard exclusive to Tesco.

• TESCO Nurture: Nurture is a quality standard exclusive to Tesco that is implemented by farms and pack houses.

• Walmart Supply Chain Security Audit Standard: It ensures that facilities have the necessary procedures and systems in place to protect the product against tampering during production, transportation and shipping.

• M&S Field to Fork This audit program is exclusive to Marks & Spencer that covers all aspects of quality and food safety within their fresh and frozen produce supply chain.

A state of the art pack house is certified for one or more of these safety standards to enter different value chains and facilitates reducing costs. It can thus facilitate trade by reducing the cost of meeting standards for farmers, promote innovations in this area, and minimize the costs of rejections by meeting quality standards. Finally, a well certified pack house must have a consistent ability to meet customer and legal food safety compliance requirements by offering trace ability services and the entire supply chain management. It reduces the possibility of contamination during transportation further reducing the possibility of rejection.

All these dynamics generated by a pack house can have profound effects on upgrading the production processes (due to large returns), distribution channels, quality of employment, and human capital in rural areas. This will generate demand for workforce development in order to meet standards, align skills with demand needs, and develop innovative new packing systems and will be a source of job diversification and upgrading of human capital in the rural areas.

Pack houses in India

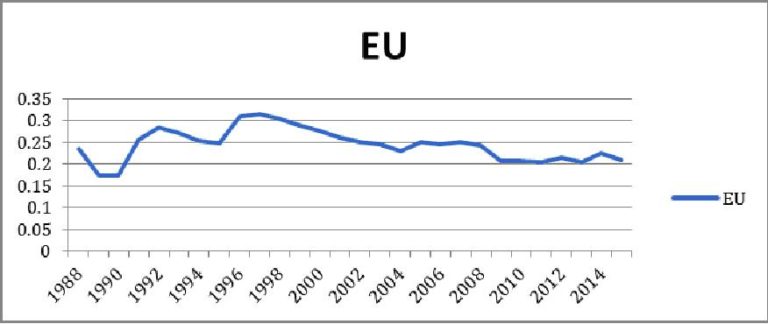

During 2013-15, India accounted for an average of 1.54% of the world fruits and vegetable exports; in 1988-1990, its share was around 1.3%. India thus barely managed to maintain its share in the export markets of fruits and vegetables. What is worrisome however is that there has been diversion of exports away from the most sophisticated markets of the US and EU to less demanding regional markets, since the late 1990s (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Share of EU and US in the exports of fruits and vegetables from India: 1988-2014

Source: Based on UNComtrade

These two regions are the largest importers of fruits and vegetables. In 2015, they accounted for 46% of the world exports with the EU being the most significant import market (36% of the world market with 10% share of the US). Both regions have shown a declining trend in their world share but the decline is sharper and secular for the EU (from 55% in the early 1990s). There could be many reasons including the rising demand from other countries but it could at least partially be attributed to high standards that the EU imposed as a way to restrict trade post WTO regime. These standards have apparently affected India’s export penetration in these markets.

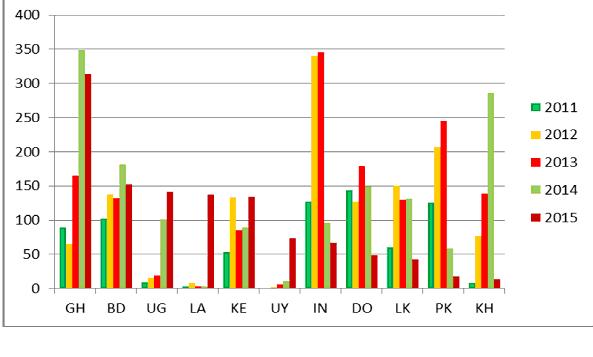

According to the EU data, India has been one of the top 10 fruits and vegetables exporting countries in terms of the number of interceptions of the consignments both for harmful organisms and other certification related reasons by the EU ( Figure 3).

Figure 3: EU based interception of fruits and vegetable exports from India Harmful organisms (A) and other reasons (B)

Source: Europhyt interceptions, Annual Report 2015

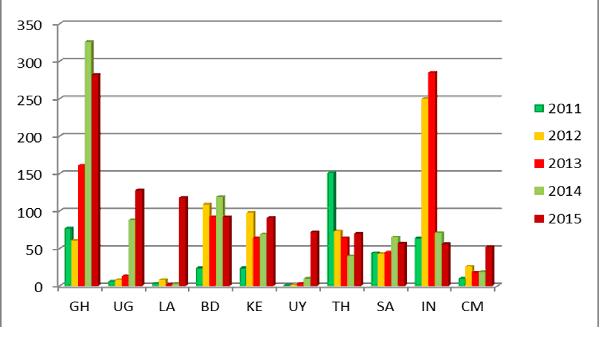

In the US also, India is one of the three countries with most import refusals; China and Mexico are the other two. While fruits and vegetables form only 13% of the total refusals in India’s case, the absolute number remains high.

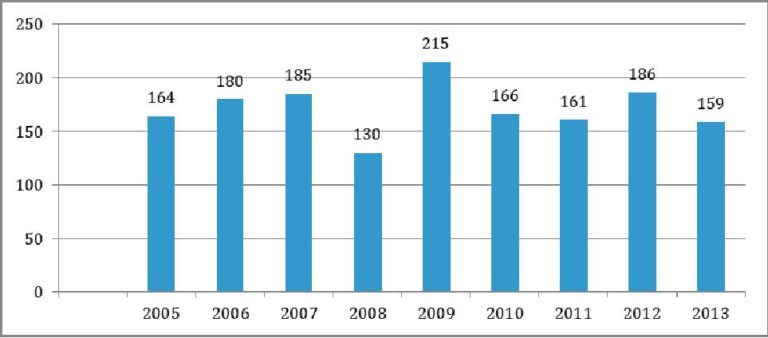

Figure 4: Shipments of vegetables and fruits refused from India by the US: 2005-2013

Source: USDA, Economic Research Service, based on U.S. Food and Drug Administration OASIS (Operational and Administrative System for Import Support) data.

In 2012, the European Union issued a regulatory calling for Phytosanitary Certificates (PSC) with each consignment of vegetables and fruits from India. Under this, the PSC was to be obtained from any of the APEDA approved laboratory and the packing had also to be done from a APEDA approved pack house. Since 2012-13. 180 pack houses have been approved by APEDA. However, in early 2014, EU authorities claimed that India’s export certification mechanism was not up to the mark. On May 1, 2014, the EU finally imposed a ban after EU’s trade authorities found 207 consignments of Indian fruits and vegetables to be infested with fruit flies. Along with Alphonso and other Indian mangoes, the ban stalled Indian exports of four vegetables: bitter gourd (karela), eggplant (brinjal), taro plant (arbi) and snake gourd (chichinda). It was followed by a ban on curry leaves and some other vegetables. The APEDA and the central government together worked together to modify the certification mechanisms according to European guidelines. While the ban on mango was lifted in January 2015, the other vegetables (except curry leaves) have got relaxation recently.

The Indian government has pledged that all food exports would be sent from APEDA-recognised pack houses. In addition, in an effort to meet the European standards, the Commerce ministry has set up 26 “special pack-houses” with the help of APEDA, for exporting vegetables and fruits to the region. According to the newspaper reports, these pack-houses will follow strict quarantine measures and will be meant exclusively for packaging and labelling fresh fruits and vegetable that are destined for EU and other markets. APEDA has also directed exporters of fruits and vegetables to route all their exports to EU through APEDA recognized pack houses only.

Beyond Trade

The fruits and vegetables sector is highly dynamic and is full of opportunities. However, it is also complex and highly professional, with requirements that need to be complied with for entry particularly in the fast growing large markets such as the EU. The demand for fresh produce continues to expand in European Union (EU) market. If India wants to grab this opportunity, it must set up ‘state of the art pack houses’ equipped with testing and innovation facilities and basic certifications in all horticulture rich areas of the country. A capacity building drive needs to be launched by arranging formal and informal training and assessment, training led by institutions that grant a certification, training by buyers, and training by governments, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). It must however be noted that for the success of pack houses a more holistic approach is required. They need to be viewed not only as facilitators of entry to European markets but also as an instrument to upgrade the quality of fruits and vegetables for consumption within India, and improve human capital and the lives of farmers engaged in this sector.

*The author is Professor at Asia Research Centre, Department of International Economics and Management, Copenhagen Business School Denmark. Can be contacted at aa.int@cbs.dk.

(This article was published in Food and Beverages Industry News, July 16-31, 2017)

This is one awesome post.Much thanks again. Cool.

I appreciate you sharing this blog.Thanks Again. Cool.

I truly appreciate this blog article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

I cannot thank you enough for the blog article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

I loved your blog.Really looking forward to read more. Want more.

Looking forward to reading more. Great article post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

I loved your article post.

I really liked your article. Really Great.

Great, thanks for sharing this blog. Fantastic.